WARNING: hostile rant against syllabus – read no further if syllabus is sacred to you.

My current attitudes toward “the” syllabus have been shaped by,

1. “a” syllabus for a recent course that was confusing, contradictory, and fragmented, and

2. by a much-quoted 2007 article “Death to the Syllabus” where Mano Singham decries “the rule-infested, punitive, controlling syllabus that is handed out to students on the first day of class.”

In Greek mythology, Procrustes was notorious for making all his captives fit his iron bed, racking them if they were too short, or amputating if they were too tall. My encounters with syllabi as a student have felt somewhat like being strapped to that bed. I feel that Procustes’ method is more suitably applied to the syllabus than to the student or to the course. I will allow that dismembering (adapting) the syllabus may be more reasonable than killing it outright. I originally wanted to make this the title of my post:

DEATH DISMEMBERMENT TO THE SYLLABUS!

but couldn’t insert HTML <strike> tags into the WordPress title.

I do appreciate Ko & Rossen’s† summary of the syllabus as a map and a schedule. I prefer to see those details woven into appropriate places in the course rather than in a separate document though. Pilar has given a good example in her screencast of putting the details where the student will be needing them.

Something fundamental inside me absolutely rebels, however, against the idea of “the contract“. Why start with that of all things? It smells so much like authoritarian, “they-owe-me” arrogance. I know. I know. That’s a distortion; but before you flame me, count the lines. What portion of “the contract” is my promise to serve up quality to the students, and how much is devoted to grounds for dismissal, disqualification, and docking points? Does the syllabus treat students as learners? Does it arouse the excitement of learning? Or does it reflect an assumption that students are not really interested in learning, will exploit every possible loophole, and cheat to get credit for doing as little as possible? Maybe we are treating students like customers, but why treat them like used-car buyers or discount-life-insurance clients who receive pages and pages of fine print circumscribing their options?

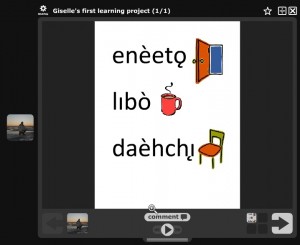

I’m going to try crafting an un-syllabus for my upcoming online language classes.

Short.

No threats.

Flexible schedule.

Collaboratively created course content and assessment criteria.

Instead of calling it a syllabus, it will be an “Introduction” or a “Welcome” section. The rest of the information I will build into the interactive course outline – made available and updated as it becomes relevant.

Who knows, in 3 months I may have cause to adjust my attitude toward legalistic syllabi.

† Ko, Susan; Rossen, Steve (2010-03-03). Teaching Online: A Practical Guide, Third Edition (p. 120, 122). Taylor & Francis. Kindle Edition.

Note: No instructors were maimed in the dismemberment of the syllabus.

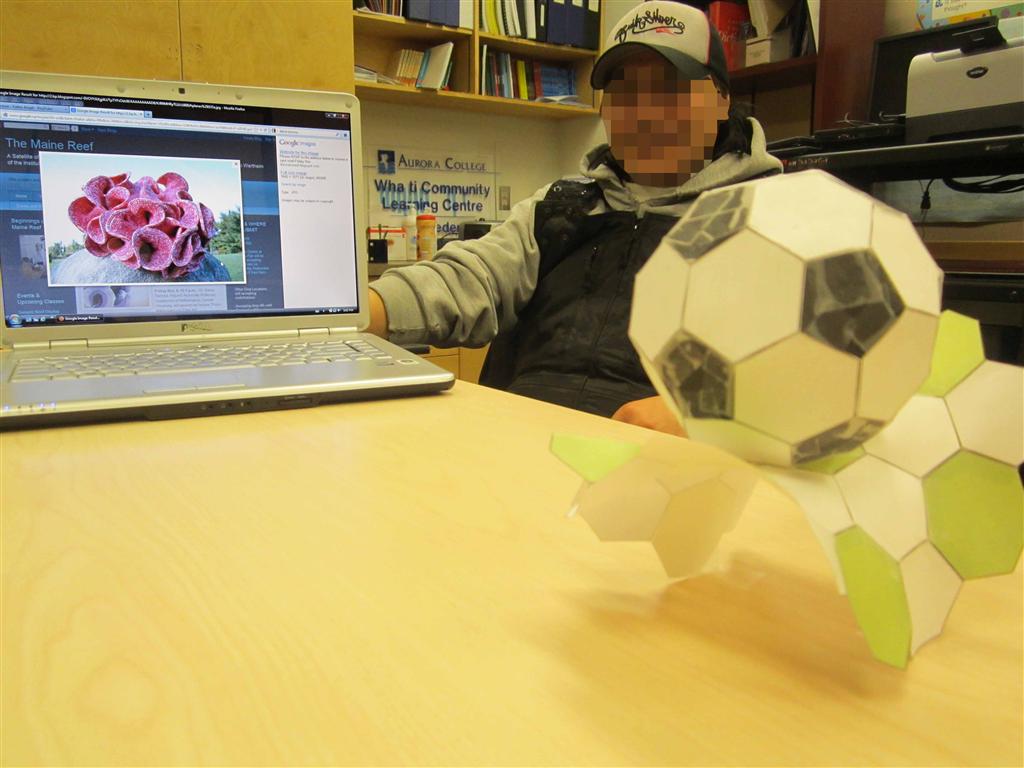

To my great delight, the Adult learners in my ABE class got caught up in making the

To my great delight, the Adult learners in my ABE class got caught up in making the